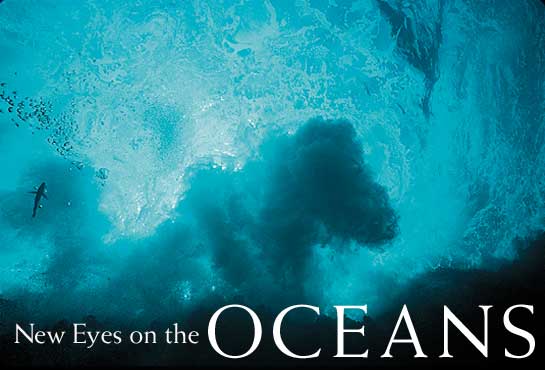

New Eyes on the OCEANS

Riding a wave of new technology, scientists are discovering more of the oceans’ secrets, including the integral role the seas play in shaping our climate.

Get a taste for what awaits you in print from this compelling excerpt.

As the R.V. Thomas G. Thompson steams south from San Diego in the winter of 2000, those of us aboard have a personal demonstration of powerful ocean movement. Heavy swells, walls of gray water from a distant storm in the North Pacific, rock and toss the ship, making the greener among us miserable with seasickness. In the computer lab amidships a notice appears on the bulletin board: “Thought problem: What is the distance to the storm that generated this swell?” It’s a good contemplative problem to take the mind off the heaving sea. But the real purpose of this cruise is to probe a more profound motion hidden beneath the endless hurrying forms of foamy waves and flying spray, a big, deep, mysterious movement of immense consequence.

The Thompson, a 274-foot (85-meter) research vessel owned by the United States Navy and operated by the University of Washington School of Oceanography, is headed south to trace the 24th parallel between North America and Hawaii. Its goal: to examine changes in the ocean since a research vessel last tracked this route 15 years earlier.

On the deck of the Thompson waits an impressive suite of oceanographic instruments, all strapped and secured against the roll and pitch of the ship. The Thompson’s main deck is given over to spacious labs humming and buzzing with banks of computers and electronic devices to measure the velocity of currents, read the surface temperature of the sea, fix the speed of wind, probe the seafloor with sound waves, and display in real time the special characteristics of a column of seawater official development website.

Some of the scientists hover about the computer screens, commenting on the sea’s patterns of heat and salt; others are in the laboratories analyzing water samples. The tools and techniques of these scientists may diverge, but their mission is one: to read the movements of water masses traveling around the planet, season to season, decade to decade, century to century and to plumb the profound effects of these, the large-scale motions of the biggest thing on Earth.

****

Rooted as we are in our firmament of soil, of continent, countryside, city, we easily forget the liquid nature of the planet. Ours is an ocean world, 70 percent water. Over the past few centuries the surface of the sea, its length and breadth, has largely been explored, its regions mapped and named. But the ocean’s third dimension, the unseen world of the deeps, and its fourth, its movements over time, have been difficult to delineate—seas of darkness.

That is beginning to change. With the help of an extraordinary set of new technological “eyes,” oceanographers have begun to pierce the ocean’s opacity, to see beneath its surface and follow its motions through time. Some of these eyes are narrow focus, measuring molecules in a small slug of water to “fingerprint” currents. Others are smart little torpedo-like floats, electronic biographers of seawater that wander the ocean’s paths. Still others are delivering a bird’s-eye perspective, viewing aloft from satellites the whole bulging blue lens of the global ocean, bouncing radar beams off the sea surface to gauge changes. Together these eyes are revealing a physical ocean more complex and changeable than we ever imagined, more like a weather system than a geological one, complete with turbulence, fronts, and strange abyssal storms.