Japan’s Winter Wildfire

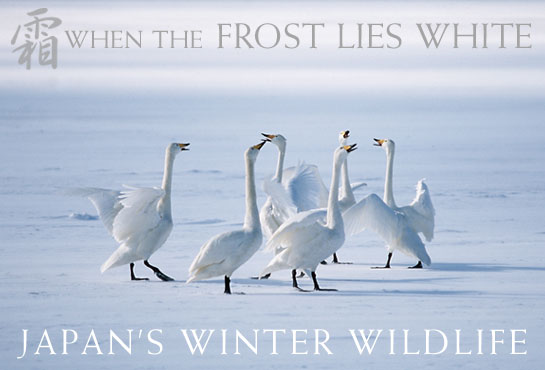

A frosted stage gathers red-crowned cranes, whooper swans, sika deer, and snow monkeys. Can Japan turn an ancient reverence for its animals into modern conservation?

Get a taste of what awaits you in print from this compelling excerpt.

In other seasons there might be 20 of us and only a few of them. But now, in the heart of winter, there are 20 of us and 150 of them. We are Homo sapiens, a gaggle of bird-watchers, scientists, and photographers; they are Grus japonensis, the rare and celebrated red-crowned crane.

The field is white and the wooded edges dark with evergreen. Out in the open in the fine snow of Hokkaido cluster the great white cranes, the black tertial plumes of their broad wings arranged over their rumps like elegant bustles. Known in Japan as tancho (red peak), the red-crowned is the second rarest crane species, after the whooping crane, with a world population of fewer than 2,500 birds. It is in other seasons fiercely territorial, but now the birds are gathered in one clangorous flock to scoop up the winter feed laid down for them by farmers. Some stalk the field or stand in pairs, lifting their bills to trumpet a shrill, rolling cry, a “unison” call that carries across the fields. One flares its wings and arches its back in a dramatic threat display to relieve the tension of crowding. A swoop of six arrives on motionless wing from their roost site in a nearby river, drop lightly to the ground amid the others, and lower their heads to pluck the scattered corn, flashing their brilliant caps of crimson like blood on snow.

The Japanese have a word, aware, for the feelings that arise from the poignant beauty of an ephemeral thing. The word refers not to the fragility or loss of the thing itself, but to the human feelings evoked by its passing. Those of us pressed against the rail are elated and grateful for this close look at the cranes concentrated here like a vision—and which, like a vision, may just as quickly vanish. No wonder people fly halfway around the world, board buses and trains and ferries, and wait patiently in the heavy snow to see these birds gather to preen and flare and dance their wild courtship dances. No wonder the crane is revered by the Japanese and so admired that their art never tires of representing it.

Only in Japan’s winter does this spectacle occur, and others as well, a striking assemblage of animals, from cranes and eagles to snow monkeys and sika deer, that endure the season’s hard tenancy in small refuges, natural and man-made, on Hokkaido and in the mountains of Japan’s main island, Honshu. Some of the animals that take shelter in these spots are abundant, even overabundant; others are rare, having been hunted to the brink of extinction or chivied out of their last natural redoubts by human pressures. Some are in the winter of their existence and endure only through the courageous efforts of a few people working against great odds.

The concentration of these creatures in small shards of habitat on a crowded island nation creates scenes of startling beauty—and sometimes, startling conflict. I’ve come to Hokkaido to learn what lessons might underlie these spectacles, what they might teach us about wildness and survival and the riddle of our own relations to nature.